Chapter 12 Java Threads and Concurrency

Understanding Threads and Concurrency¶

Before we dive into the technicalities of using threads and managing concurrency in Java, let's build a solid understanding of the fundamental concepts.

What is a Thread?¶

A thread in computer science is short for a thread of execution. Threads are a way for a program to split itself into two or more concurrently running tasks. Threads are lighter than processes, and share the same memory space, which means they can communicate with each other more easily than if they were separate processes.

In Java, a thread is an instance of the class java.lang.Thread. Java programs come with several threads that run in the background to perform actions such as garbage collection. Additionally, you can create your own threads to execute complex or time-consuming operations without blocking the main thread and freezing your application.

Here's an example of creating a new thread in Java:

// Create a Runnable

Runnable myRunnable = new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

// Code to run in new thread

}

};

// Create a Thread

Thread myThread = new Thread(myRunnable);

// Start the Thread

myThread.start();

What is Concurrency?¶

Concurrency is the ability of different parts or units of a program, algorithm, or problem to be executed out-of-order or in partial order, without affecting the final outcome. It's a property of systems in which several independent tasks are executing concurrently.

In Java, concurrency is often accomplished using threads. A multi-threaded program contains two or more parts that can run concurrently. Each part of such a program is called a thread, and each thread defines a separate path of execution.

Concurrency can improve the performance of software, making it run faster, or improving its ability to be responsive. This is particularly important in applications involving graphical user interfaces, real-time systems, or those running on multi-core processors.

Difference Between Process and Thread¶

A process and a thread are independent sequences of execution, the typical difference is that threads (of the same process) run in a shared memory space, while processes run in separate memory spaces.

-

A process has a self-contained execution environment. It has a complete, private set of basic run-time resources; in particular, each process has its own memory space.

-

Threads are sometimes called lightweight processes. Both processes and threads provide an execution environment, but creating a new thread requires fewer resources than creating a new process.

In a nutshell, a thread is a subset of a process. Multiple threads within a process share the same data space with the main thread and can therefore share information or communicate with each other more easily than if they were separate processes.

Both threads and processes are fundamental resources that Java programming language programmers use to design applications that require multiple tasks to occur simultaneously.

Creating and Managing Threads in Java¶

In Java, there are two primary ways to create a thread:

Creating Threads by Extending Thread Class¶

The Thread class itself implements Runnable, though it's more common to create a new class that implements Runnable. Here is how you can create a thread by extending the Thread class:

class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

// Code to execute in this thread

}

}

// To use it:

MyThread myThread = new MyThread();

myThread.start();

The run() method is where you define the code that the thread will execute. The start() method is used to begin the thread's execution.

Creating Threads by Implementing Runnable Interface¶

Another way to create a thread is to implement the Runnable interface and pass an instance of that class to a Thread:

class MyRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

// Code to execute in this thread

}

}

// To use it:

Thread thread = new Thread(new MyRunnable());

thread.start();

This approach is generally preferred over extending Thread because it allows the class to extend another class, as Java only allows single class inheritance.

Managing Thread's Life Cycle¶

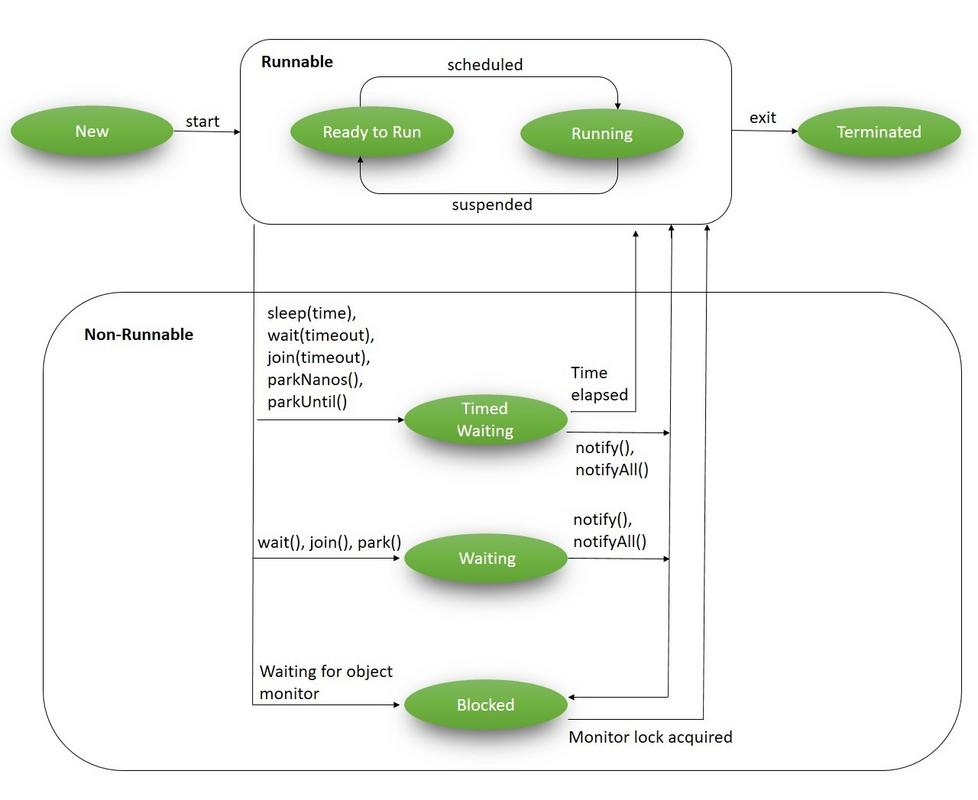

A thread goes through various stages in its life cycle. For example, a thread is born, started, runs, and then dies. The following diagram shows the complete life cycle of a thread.

-

New: A new thread begins its life cycle in the new state. It remains in this state until the program starts the thread. It is also considered to be in the "new" state if it has been stopped and not yet restarted.

-

Runnable: After a newly born thread is started, the thread becomes runnable. A thread in this state is considered to be executing its task.

-

Waiting: Sometimes, a thread transitions to the waiting state while the thread waits for another thread to perform a task. A thread transitions back to the runnable state only when another thread signals the waiting thread to continue executing.

-

Timed Waiting: A runnable thread can enter the timed waiting state for a specified interval of time. A thread in this state transitions back to the runnable state when that time interval expires or when the event it is waiting for occurs.

-

Terminated (Dead): A runnable thread enters the terminated state when it completes its task or when it encounters an unrecoverable error. The thread is considered dead, and this cannot be restarted.

It's important to understand these states and manage them appropriately to ensure your applications are behaving correctly and efficiently. Each thread in Java is created and controlled by the java.lang.Thread class, which provides methods to start and stop threads, and to check and control their state.

Synchronization and Inter-thread Communication¶

Understanding Synchronization¶

Synchronization in Java is an important feature that allows only one thread to access a block of code at a time. It is used to prevent race conditions, which can cause unpredictable results and other problematic behaviors in multithreaded programs.

For instance, if two threads try to write to the same variable at the same time, the final value of the variable may depend on which thread writes last, and this might not be predictable or desirable. Synchronization ensures that these threads don't interfere with each other.

synchronized Keyword¶

The synchronized keyword in Java creates a block of code known as a synchronized block, which is marked as "locked" while a thread is inside it. Other threads that attempt to enter this block are blocked until the thread inside the block exits the block.

Here's an example of how to use synchronized:

public class Counter {

private int count = 0;

public synchronized void increment() {

count++;

}

}

In this example, the increment() method is synchronized, so only one thread at a time can increment count.

Inter-thread Communication using wait(), notify(), and notifyAll()¶

Java provides a mechanism for threads to communicate with each other through the methods wait(), notify(), and notifyAll().

-

The

wait()method tells the current thread to give up the monitor and go to sleep until some other thread enters the same monitor and callsnotify()ornotifyAll(). -

The

notify()method wakes up the first thread that calledwait()on the same object. -

The

notifyAll()method wakes up all the threads that calledwait()on the same object. The highest priority thread will run first.

These methods are used to ensure that a thread does not use resources prematurely, and that the relevant task has completed before the resources are used.

Thread Pool and Executors in Java¶

What is a Thread Pool?¶

A thread pool is a group of pre-instantiated, idle threads that stand ready to be given work. These are worker threads that exist separate from the Runnable and Callable tasks they execute.

Creating a new thread for each task can be expensive in terms of system memory and time, and can also lead to too many threads competing for CPU resources. A thread pool can help manage these resources: we can limit the number of total threads and can reuse threads once they finish their tasks.

Executors Framework¶

The java.util.concurrent.Executors class provides factory and utility methods for the various classes in the Java Concurrency Framework, including the thread pool.

Here's a simple example of creating a fixed thread pool:

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(5);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

Runnable worker = new MyRunnable();

executor.execute(worker);

}

executor.shutdown();

while (!executor.isTerminated()) {

}

System.out.println("Finished all threads");

In this example, we're creating a fixed thread pool of five worker threads. We then submit ten tasks to this pool and shut it down once we've submitted all the tasks. The tasks will be executed by the five threads in the pool.

Scheduled Task Executor¶

The Executors class also provides methods for scheduling tasks to run after a delay, or to be repeatedly executed.

ScheduledExecutorService executor = Executors.newScheduledThreadPool(1);

Runnable task = new MyRunnable();

ScheduledFuture<?> future = executor.schedule(task, 5, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

In this example, a single-threaded executor is created. The task will be executed after a delay of 5 seconds.

The ScheduledExecutorService also provides support for periodic execution of tasks, via the scheduleAtFixedRate() and scheduleWithFixedDelay() methods.

Locks in Java Concurrency¶

In Java, the term lock refers to a thread's ability to exclusively access a section of code or resource. When a thread has a lock, no other thread can access the locked region until the lock is released.

The Basic Principle of Lock¶

A lock protects shared data from being concurrently accessed by multiple threads. The basic principle of a lock is:

- Only one thread can hold the lock at a time.

- A thread can acquire the lock before accessing shared data.

- If other threads try to acquire the same lock, they will be blocked until the thread holding the lock releases it.

The Lock Interface and its Methods¶

The Lock interface was introduced in Java 1.5 and provides more extensive locking operations than can be obtained with synchronized methods and statements. This interface allows more flexible structuring and can support multiple associated Condition objects.

Here are some important methods provided by the Lock interface:

lock(): Acquires the lock, if it's available. If the lock isn't available, it waits until it becomes available.tryLock(): Tries to acquire the lock. If it can't, it doesn't wait, but simply returnsfalse.unlock(): Releases the lock.

It's important to always release the lock in a finally block to ensure the lock is released even if an exception is thrown in the try block.

ReentrantLock Class¶

The ReentrantLock class is an implementation of the Lock interface that has the same basic behavior and semantics as the implicit monitor lock accessed using synchronized, but with extended capabilities.

A ReentrantLock is "reentrant" because it allows a thread to acquire the same lock multiple times without causing a deadlock.

ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void increment() {

lock.lock(); // block until the lock is available

try {

count++;

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // always release the lock in the finally block

}

}

In this example, the increment method is locked by the lock.lock() method. If any other thread attempts to access this method while it's locked, it will be blocked until the lock.unlock() method is invoked.

Remember, using ReentrantLock can be more flexible than using synchronized, but it also requires more care since you must manually release the lock by calling unlock and this often involves writing more code.

Atomic Variables and Concurrent Collections¶

Understanding Atomic Variables¶

Atomic variables in Java are used in multithreaded environments to perform operations on a single variable without using synchronized. The java.util.concurrent.atomic package defines classes that support atomic operations on single variables. All atomic operations are performed using volatile semantics, meaning that they are thread-safe and do not suffer from race conditions.

Classes in java.util.concurrent.atomic Package¶

This package includes a number of classes that support lock-free, thread-safe programming on single variables:

AtomicBoolean: A boolean value that may be updated atomically.AtomicInteger: An int value that may be updated atomically.AtomicIntegerArray: An int array in which elements may be updated atomically.AtomicLong: A long value that may be updated atomically.AtomicLongArray: A long array in which elements may be updated atomically.

For example:

AtomicInteger atomicInt = new AtomicInteger(0);

int theValue = atomicInt.incrementAndGet();

Here, incrementAndGet is an atomic operation, so it's safe to call in a multithreaded environment without the need for further synchronization.

Concurrent Collection Interfaces and Classes¶

The Java Concurrency API also includes a number of concurrent collections in the java.util.concurrent package. These collections help to improve the scalability of your Java application.

Some of the key interfaces and classes are:

BlockingQueue: Defines a first-in-first-out data structure that blocks or times out when you attempt to add to the queue when it's full, or retrieve from the queue when it's empty.ConcurrentMap: A type ofMapthat can handle concurrent use by multiple threads.ConcurrentHashMap: An implementation ofConcurrentMap.CopyOnWriteArrayList: A thread-safe variant ofArrayListin which all mutative operations (add,set, and so on) are implemented by making a fresh copy.

ConcurrentMap<String, String> concurrentMap = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

concurrentMap.put("Key", "Value");

In this example, concurrentMap is a thread-safe variant of HashMap. Modifications (put and remove) are expensive but retrieval operations (get and contains) are very efficient and high concurrency among updates is maintained.

Future and Callable Interfaces¶

In Java, the Future and Callable interfaces represent the result of an asynchronous computation.

Understanding Future and Callable¶

A Callable is a task that returns a value and throws exceptions. It's designed to have a finer control over threads as compared to Runnable, mainly because it can return computed results.

A Future represents the pending result of a computation. It provides methods to check if the computation is complete, to wait for the computation to get complete, and to retrieve the result of the computation.

The primary method in the Callable interface is call(), which is implemented by the thread. The call() method can return a value or throw an exception.

The Future interface has methods such as isDone(), which returns true if the Callable has completed executing, and get(), which retrieves the result of the computation when it's ready.

Use Cases and Examples¶

Consider a scenario where we want to fetch data from a database, perform some computations, and then store the result back in the database. All these operations can take considerable time, and we might not want to wait for each one to complete before starting the next. This is where Callable and Future come in handy.

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(10);

Callable<Integer> task = () -> {

try {

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(1);

return 123;

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new IllegalStateException("task interrupted", e);

}

};

Future<Integer> future = executor.submit(task);

System.out.println("future done? " + future.isDone());

Integer result = future.get(); // this will block if the future is not done

System.out.println("future done? " + future.isDone());

System.out.println("result: " + result);

Fork/Join Framework in Java¶

The Fork/Join Framework in Java is designed for work that can be broken down into smaller tasks and the results of those tasks combined to produce the final result.

Understanding Fork/Join Framework¶

The idea behind the Fork/Join Framework is that if a task is too complex, it can be divided (forked) into smaller subtasks that can be executed concurrently. Once the subtasks finish their execution, their results are joined together.

The Fork/Join Framework uses a ForkJoinPool which extends AbstractExecutorService. It works on the principle of "work-stealing" where all the worker threads in the pool attempt to find and execute tasks submitted to the pool and/or created by other active tasks (eventually blocking waiting for work if none exist).

ForkJoinTask Class¶

ForkJoinTask is an abstract base class that essentially represents a unit of work in the Fork/Join Framework. Two subclasses of ForkJoinTask are commonly used: RecursiveTask and RecursiveAction.

RecursiveTask is used when the task returns a result, and RecursiveAction is used when the task doesn't need to return a result.

Use Cases and Examples¶

Consider a scenario where you have a large array of numbers and you want to compute the sum of these numbers. This task can be broken down into subtasks by using the Fork/Join Framework.

class MyRecursiveTask extends RecursiveTask<Long> {

private final long[] numbers;

private final int start;

private final int end;

MyRecursiveTask(long[] numbers, int start, int end) {

this.numbers = numbers;

this.start = start;

this.end = end;

}

@Override

protected Long compute() {

int length = end - start;

if (length <= 2) {

return computeDirectly();

} else {

int middle = start + length / 2;

MyRecursiveTask task1 = new MyRecursiveTask(numbers, start, middle);

task1.fork(); // forked task will be executed by another thread

MyRecursiveTask task2 = new MyRecursiveTask(numbers, middle, end);

Long result2 = task2.compute();

Long result1 = task1.join();

return result1 + result2;

}

}

private long computeDirectly() {

long sum = 0;

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

sum += numbers[i];

}

return sum;

}

}

This code illustrates a simple use case of the Fork/Join Framework. The compute() method checks the length of the task and if it's small enough, it computes the task directly. Otherwise, it splits the task into two subtasks.

Deadlocks, Starvation, and Livelocks in Java¶

Multithreading can bring many benefits to a program, but it also has its challenges. Three common challenges that come with multithreading are deadlocks, starvation, and livelocks.

Understanding Deadlocks¶

A deadlock is a situation where two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other to relinquish a lock. Deadlocks occur when multiple threads need the same locks but obtain them in different orders. A Java multithreaded program may face the issue of deadlock, which can cause the program to come to a standstill.

Here's a simple example illustrating a deadlock:

final String resource1 = "resource1";

final String resource2 = "resource2";

Thread thread1 = new Thread(() -> {

synchronized (resource1) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: locked resource 1");

try { Thread.sleep(100);} catch (Exception e) {}

synchronized (resource2) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: locked resource 2");

}

}

});

Thread thread2 = new Thread(() -> {

synchronized (resource2) {

System.out.println("Thread 2: locked resource 2");

try { Thread.sleep(100);} catch (Exception e) {}

synchronized (resource1) {

System.out.println("Thread 2: locked resource 1");

}

}

});

thread1.start();

thread2.start();

Understanding Starvation¶

Starvation occurs when a thread is unable to gain regular access to shared resources and is unable to make progress. This happens when shared resources are made unavailable for long periods due to "greedy" threads. In other words, a thread becomes "starved" of the resources it needs for its execution.

Understanding Livelocks¶

A livelock is similar to a deadlock, except that the states of the threads involved in the livelock constantly change with regard to each other. This, however, doesn't lead to any progress as the threads can't move forward. The threads are unable to make further steps towards their goals, because they are too busy responding to each other.

How to Avoid Them?¶

-

Deadlock can be avoided by ensuring that a fixed order is followed while acquiring the locks. In the example given above, if both threads attempt to acquire the locks in the same order (

resource1thenresource2), the deadlock would not occur. -

Starvation can be avoided by implementing a "fairness" policy where each thread gets an equal opportunity to access shared resources. In Java, we can enforce fairness using a

ReentrantLockand setting its fairness property totrue. -

Livelock can be avoided by making the threads more cooperative and less responsive. That means, instead of continuously trying to perform their tasks, the threads should yield control and give other threads the chance to proceed.

It is important to note that these problems aren't always easy to detect or solve, especially in complex systems. Good design and understanding of the multithreading process are crucial to prevent these issues.

Understanding CompletableFuture¶

A CompletableFuture is a Future that may be explicitly completed by setting its value and status, and may be used as a CompletionStage, supporting dependent functions and actions that trigger upon its completion. Introduced in Java 8, CompletableFuture has been continuously improved, and with Java 20, it's become a key feature for asynchronous programming in Java.

Basics of CompletableFuture¶

A CompletableFuture can be seen as a promise of a computation result to be available in the future. This allows you to write non-blocking code and perform other tasks while waiting for the asynchronous operation to complete.

Here is a basic example of creating a CompletableFuture:

CompletableFuture<String> future = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

// Simulate a long-running task

try {

Thread.sleep(3000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new IllegalStateException(e);

}

// Return result of the long-running task

return "Result of the asynchronous computation";

});

In this example, CompletableFuture.supplyAsync() is used to create a CompletableFuture that completes with the value provided by the Supplier (() -> {...}).

Method Reference and CompletableFuture¶

Java 20 brings a new way of using CompletableFuture with the method reference. A method reference is described using "::" symbol. It provides a way to reference methods directly using their names. This way, we can make our code more readable and compact. Here is an example of using CompletableFuture with method reference:

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::someLongRunningTask)

.thenApply(this::anotherTask)

.thenAccept(this::consumeResult);

This is a simple yet powerful chain of CompletableFuture tasks. It starts an async task someLongRunningTask, applies another task anotherTask to the result of the first task, and then consumes the result with consumeResult.

Combining CompletableFuture Objects¶

You can also combine multiple CompletableFuture objects into a single computational stage. There are several ways to achieve this, depending on what you want:

-

thenCompose: Returns a newCompletableFuturethat, when this stage completes normally, is executed with this stage's result as the argument to the supplied function. -

thenCombine: Returns a newCompletableFuturethat, when both this and the other given stage complete normally, is executed with the two results as arguments to the supplied function.

CompletableFuture<String> future1 = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Hello");

CompletableFuture<String> future2 = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> " World");

CompletableFuture<String> combinedFuture = future1.thenCombine(future2, (s1, s2) -> s1 + s2);

combinedFuture.get(); // returns "Hello World"

In the example above, future1 and future2 are combined into combinedFuture using the thenCombine method. The lambda (s1, s2) -> s1 + s2 is applied when both future1 and future2 complete.

Mastering CompletableFuture can significantly boost your Java multithreaded programming skills, allowing you to write efficient, non-blocking, and fast code.

Key Takeaways¶

- Understanding of threads and concurrency is essential for developing efficient Java applications.

- Care must be taken while handling shared resources in a multithreaded environment.

- Explicit locks provide more control compared to implicit locks provided by

synchronizedkeyword. - CompletableFuture and Executors framework can boost the performance of your Java applications by leveraging multi-core processors.

- Understanding and avoiding deadlock, starvation, and livelock situations is crucial for creating bug-free multithreaded applications.